* *

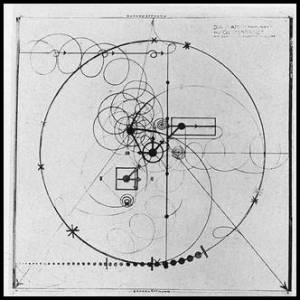

OPEN DIAGRAM – Diagram for Gesture Dance – Oskar Schlemmer – 1926

THE DIAGRAM OF DIGITAL PLATFORMS

- Genaro, E. & Denani, G. (2021). “A diagramática das plataformas digitais.” Revista Famecos, v. 28, p. e40024. [Online] Available at: https://revistaseletronicas.pucrs.br/index.php/revistafamecos/article/view/40024

Introduction

The current corporate models of digital platforms and their data centers are formidable machines for accelerating and controlling flows, energies, investments, and speculations. This research article explores the platforms’ diagrammatic nature—a virtual and shapeless system that manages and serves lives in the name of total ‘freedom of speech.’ The study is grounded in four modulation mechanisms proposed by David Savat: the recognition of patterns, the anticipation of activity, the organization of antitheses, and the programming of flows.

Based on this framework, the article establishes hypotheses, theses, and reflections on the platforms’ power of disruption, time-populating, and distributed controls, as well as their various associated issues. This leads to a discussion of the satisfied, submissive, and resigned user and the limitations of using terms like manipulation, responsibility, and privacy.

New Technological Layer

A new layer of global industrialization, often called Industry 4.0, is being superimposed on existing infrastructures. This new stage is characterized by automated production, intensive data use, and communication between connected devices.

The socio-technical systems—which link human groups and technical objects via infrastructures known as digital platforms—are experiencing unstable mechanisms of informational and geopolitical decentralization and recentralization. This is similar to how agriculture was transformed by electronic machines and synthetic chemistry, and how industrial centers were affected by telecommunication networks. On these platforms, production, distribution, and marketing processes are much more widespread and disseminated, combining scale and long-tail economies.

Digital platforms organize, coordinate, and connect producers, customers, advertisers, providers, and products across the internet. Consequently, platforms are primarily defined by their ability to create and exploit audiences and market niches, often by offering services and products that previously existed only in embryonic forms or as unexplored market possibilities.

It is important to highlight the unprecedented monopolistic effects of informational and commercial power that have emerged since the 1990s from an infrastructural and ideological core in Silicon Valley. A similar phenomenon is now occurring in the Chinese province of Guangdong, specifically in Shenzhen, involving the creation and exploitation of surveillance technologies and electronic currency.

This article focuses on explaining some specific parameters of the logic and character of digital platforms, examining essential hypotheses, theses, and reflections on their structures.

Disruption

The most emblematic, well-known, and monopolizing example of digital platforms is Uber Technologies Inc. Although a private transport market with independent taxi drivers and cooperatives existed before its advent, one can affirm that Uber’s technological and business model was disruptive—despite the often ostentatious, rhetorical, and vague use of the term. This is because, based on the concept of e-hailing, it disrupted conventions and possibilities of urban mobility at multiple levels. The convenience of calling a driver, knowing the price in advance, tracking the ride in real time, evaluating the driver’s performance, and paying seamlessly make the service easy to use—almost magical. Such disruption affects not only the customer experience but the service as a whole. Anyone, anywhere, can become a private driver (a process of diffusion and capillarization). The previous monopolistic system (via municipal bidding, permits, or licenses), which had once made the taxi profession minimally attractive, became archaic, as did the stable monthly income it provided, since prices—interweaving market dynamics and long-tail economies—are now determined by the algorithmic codes of the company that owns the platform.

However, another example—though not precisely of disruption—concerns a particular category of work. This is the case of food delivery platforms such as Uber Eats (Uber Technologies Inc.), Rappi (Colombia), and iFood (Movile Group, Brazil), which can be seen as mediators between fast-food companies and their customers, since their applications function as a digital marketplace of deals. Nevertheless, such platforms foster an unskilled workforce composed of delivery workers whose elementary task is to move from point A to point B in the shortest time possible. Needless to say, the autonomy and ease of becoming a delivery person are directly proportional to the precariousness of the work. The same applies to drivers. Thus, if on the one hand it is reasonable to assume that no one wishes to build a career in this field, on the other hand the aggressive tendency of these platforms to extract value from people who would otherwise struggle to find another source of income (particularly in contexts shaped by neoliberal and deindustrialization policies) is evident, as in the Brazilian case.

The third and final example concerns vehicles available for urban mobility, such as scooters and bicycles. Companies such as Jump (Uber Technologies Inc.) and Grin (Grow Mobility Inc.) provide vehicles for rent, charging a specific fee for each use. In this way, in a single act of food delivery, the business owner, the delivery worker, and the client become absorbed in the disruption produced by the chain of platforms that make the service possible: the Uber Eats application, which connects the three; Uber Jump, which provides rapid transportation for the delivery worker; and Google Maps, which supplies the best directions. The list of mobility platforms continues to grow—for instance, Airbnb (Airbnb, Inc., 2008), through which the client-traveler obtains lodging—while new facilities and needs emerge, expanding the ubiquity of platforms in their many modes of exploiting subjectivities: professional (LinkedIn, LinkedIn Corporation Inc., 2002), dating (Tinder, Tinder Inc., 2012), photography (Instagram, Facebook, Inc., 2009), video (YouTube, Google LLC, 2005), movies (Netflix, Netflix Inc., 1997), music (Spotify, Spotify Technology S.A., 2006), social media (Facebook, Facebook, Inc., 2004), messaging (WhatsApp, Facebook, Inc., 2009), microblogging (Twitter, Twitter, Inc., 2006), micro-video (TikTok, Beijing ByteDance Technology Co. Ltd., 2016), and commodities (Amazon, Amazon.com Inc., 1994; Mercado Livre, MercadoLibre Inc., 1999).

Time populating

Therefore, it is possible to understand that an expressive parameter of platforms—especially those of mobility—is the precariousness of work, the transformation of urban space, and the control of workforce, infrastructure, and design that they mobilize. This alone already arouses a maelstrom of complex political and academic issues and agendas, particularly for urban planners and sociologists.

Moreover, all the aforementioned platforms—especially Facebook, Amazon, and Google—rely on the data generated by their users as a fundamental element of their business models. Through the accumulation and transformation of data, it becomes possible to generate economic value: a mass of consumers with desires to be satisfied (and often produced), alongside a mass of have-nots mobilized to earn a minimal hourly wage. Delivery workers and drivers are prominent examples, since they provide services and transport in a gray zone between public and private spheres of the so-called sharing economy. Yet insecurity lies in wait for everyone. One only needs to recall Amazon Mechanical Turk and similar services such as Leapforce and click farms, which continue “exploiting the new lands of the Internet with no need for strict enclosures and no need to produce content too” (Pasquinelli, 2009, p. 11)—measuring only the collective intelligence that produced the data. In the new theory of capitalist rent, data captured from users functions as a reservoir of traces from which meanings are extracted. These essentially reveal probabilities of possible futures for decision-making that may be used either to reinforce a given trend or to avoid it.

The axiom is clear: “bodies that do not generate code, at least from the perspective of modulation, do not exist. The more wired the world becomes, the more code bodies will generate, including on the biological level” (Savat, 2013, p. 44). Codes overflow their initial infrastructures, encompassing logistical, sexual-affective, political, and other systems. Yet this does not occur without recognizing and capturing specific code patterns—whether in a user browsing images and profiles on Tinder, or in a driver navigating the road network with the guidance of Waze (Waze Mobile, 2006; Google LLC, since 2013) or Google Maps (Google LLC, 2005).

The diagram, Deleuze reminds us, “[…] is different from structure in so far as the alliances weave a supple and transversal network that is perpendicular to vertical structure; [it is] an unstable physical system that is in perpetual disequilibrium instead of a closed […]” (Deleuze, 2006, pp. 35–36). As cartographies of capture and potentiation, modulation diagrams—though they do not predefine—are able to guide in a much more capillary and immersive way, at an asignificant, machinic, non-representative, or non-discursive level of the subject (Lazzarato, 2014). Unlike the disciplinary diagram, capture through modulation does not occur in populated spaces such as prisons, factories, or schools, but rather through the populating of time. This is an elementary aspect of the modulation power of control societies, and it can be understood through four mechanisms, as David Savat (2009; 2013) clarifies: the recognition of patterns, the anticipation of activity, the organization of antitheses, and the programming of flows.

It follows that these mechanisms operate across different parts of a platform’s infrastructure. At the user level, codes manifest themselves in the application’s graphical interface and in the metadata the user consents to through the Terms of Use. From this emerge the diagrammatic arrangements—an inviolable rule of platforms—of subjectivation through the capture of pre-individual somatic domains, prior to the formation of emotions and consciousness (Massumi, 2002). These processes arise through intensive and recursive dynamics in which unconscious activity and affect intertwine within computational temporalities.

Distributed control systems

Intensive and recursive processes, however, are not only user-focused. The different ways of structuring computational algorithms, databases, and other digital objects allow for flexibility in the standardization and organization of projects as well as in software development teams. The software development technology Git—and the GitHub platform (GitHub, Inc., 2008; Microsoft Corporation, since 2018)—marks an inflection point in the modulation of the subject by introducing a distributed version-control system. The possibility of participating in a collaborative development environment—analyzing, testing, and upgrading code—expands the production space from the corporate office to the developer’s bedroom, while also fracturing temporal continuity. This occurs because the prioritization of different parts of a project reacts to forces such as deadlines, prescriptions regarding the minimum viable product, and other elements that qualify the production of the embryonic diagrammatic device of the contemporary world: software.

The following mechanisms, subsumed under the first, make it unique. The second—anticipation of activity—has become increasingly evident in recent years with the popularization of artificial intelligence technologies and their application in expert systems to automate decision-making processes. In addition to its corporate uses, this mechanism has been criticized for its potential implementation in American courts, where it risked automating racist bias against Black people (Noble, 2018). Beyond this nefarious use of technology to reproduce historical inequalities, such incidents can also be interpreted as a countermovement marking the transition from discipline to control. The individual is more central to discipline than to modulation, since modulation predicts patterns rather than inscribing attributes and behaviors into the body as a dividual element. Indeed, the bias of a database—or of an artificial intelligence model trained on a skewed dataset—cannot probabilistically anticipate the next point on a chart; it merely reiterates previously given data. In this sense, it remains closer to a disciplinary architecture than to the diagram of modulation and control.

Working as a game; entertainment as an obligation

Through a chronology of governments—from sovereign to disciplinary, culminating in the government of control—it is possible to affirm that, just as disciplinary power released the body once subjected to sovereignty into a productive potential aligned with industrial capitalism, modulatory power releases the disciplined body into new forms of value extraction. Understanding this orchestrated liberation, which operates upon the temporality of subjects, requires critique through the notion of political organology, capable of articulating autonomy, metastability, and ethics. Yet the current situation is fragile. One symptom of this liberation is the apparent collapse of distinctions between activities that were once (problematically) well defined under disciplinary power: study-training, work, and leisure.

The contemporary experience of these activities’ hybrid character is visible in the gamification boom of the mid-2010s, as well as in the snowballing of entertainment consumption. With respect to the latter, statements from the CEOs of Netflix and Spotify are symptomatic: while one claimed that his main competitor is sleep (Sulleyman, 2017), the other asserted that musicians must adapt to producing new songs more frequently (Darville, 2020). As the next frontier of capitalist extraction, the circadian cycle points toward a reconfiguration of reception itself as an epistemological category within communication studies.

In other words, even if the act of looking confers a certain similarity between the streaming user and the television viewer, they diverge at first glance because of the different materialities articulated by each medium. A prime-time soap opera (and the very concept of prime time) presupposes a closed symbolic circuit between production and consumption: the viewer negotiates meaning, re-signifies it within a local context, and ultimately delivers his or her attention to the show’s sponsors. The streaming user, by contrast, is not sold in “batches” of synchronous, collective attention, but rather in fragments: through recombinations of signs encoded in binary code, geographic coordinates, retention after the first few minutes, and countless other data points. The abundance of available content functions as an almost irresistible invitation to dissolve into diverse metrics.

Reception feedback—whether in the form of playback speed, ratings, recommendations, or an ever-expanding catalog—and the hypertrophy of this circuit diminish the significance of approaching the user as a subject of meaning, and instead highlight their condition as a subject of extraction. To work as if it were a game, to entertain oneself as if it were an obligation (Savat’s organization of antitheses), is to experience the same crumbling of time once endured by the phonographic market under Spotify.

Because the logic of platforms is not a linear sequence of procedures but rather a constellation of points distributed in multidimensional space, the search for a minimal metastability within digital platforms becomes a matter of survival—particularly for marketing. The constitution and continuous maintenance of metastability is what Savat calls the programming of flows. This manifests most visibly in the composition of users’ social media feeds. Design and control over heterogeneity characterize these flows, employing equally heterogeneous calculations—content curators, artificial intelligence systems, and management methodologies—often metonymically reduced to the elusive term algorithm.

Sophistication, criticism and inquietation

Population control through digital platforms is, in this sense, an exemplary configuration of the contemporary exercise of power. It is sophisticated, since its soft power operates at a machinic, asignificant level, abstracting from ideology—the power that “is no longer encompassing [,] it no longer defines the global mode of functioning of power” (Massumi, 2002, p. 42). It is also irreversible, given the efficiency of its elementary technological logic (after all, choosing to call a taxi rather than an Uber, or paying for an e-mail server, would amount to eccentric militancy). It is critique-worthy in its political-economic logic, insofar as it ratifies the neoliberal norm of unrestricted delegation of power to corporations, to the detriment of civil society and the public authority of organological decision-making. Finally, it is unsettling, philosophically and politically, since such modular control is openly nurtured—an effect of the current inability to organize and constitute more supportive and democratic values and policies—through contemporary subjectivities themselves.

Nevertheless, modular control is not unidirectional and does not serve a single conglomerate. As corporate economic groups, the owners of digital platforms manage capital and may oppose, cooperate, or merge in their intercapitalist relations. A given database, therefore, can itself become a commodity—sold, stolen, or used by an interested party other than the platform that initially produced it. Its price depends on its potential to extract relations among the data it contains. In short, the algorithms that analyze these massive datasets function like sieves separating gold from worthless minerals.

The give-and-take scenario of presumed gratuity—platforms offering partial or full access to services while user-workers generate tons of data-tasks that both control and exploit them—is the ace in the hole of the new business model. Here criticism and unease are easier to grasp. The conveniences, autonomy, and gratuities offered by platforms are welcomed by contemporary subjectivities as rational economic choices. Taking a stance on one’s self-produced data—or on the (perfidious) freedom of work itself—is often treated as irrelevant or inconvenient at several levels. This dynamic reflects the surprising and unapproachable “power of applications,” which exploits a subtle satisfaction: former ways of listening to music, ordering food, or meeting a sexual partner now appear costly when compared with new habits intertwined with the smartphone interface. In turn, the mass of data is consigned to perfecting that very satisfaction.

Thus, the success of social media lies in constantly renewing discursive affinity with users and expanding opportunities for work and consumption—at the expense of their silent and ghostly contributions, which are considered negligible by users who remain satisfied, devoted, and resigned.

Beyond manipulation

The character and logic of digital platforms—culminating in atmospheres of disruption, modular control, consignment, and resignation—today exhibit, across contexts, acute sociopolitical aftereffects. These are notably tied both to the deconstruction of ideals of civility and democracy, as seen in several countries, and to the channeling of power through platforms—especially social media—for specific ends.

The “electoral disruptions” expressed in Donald Trump’s election in the United States, the Brexit victory in the United Kingdom, and, more recently, Jair Bolsonaro’s election in Brazil, are troubling not only for their direct political consequences but, more profoundly, for the open display of disbelief in republican, democratic, and scientific institutions. These disruptions are rooted in socio-affective phenomena—reactive, illiberal, provincial, conservative—that reflect counterfeit operating modes of contemporary subjectivity. In particular, they revealed the power of databases to modulate political affections on a population scale, in ways both excessive and deeply questionable.

As a rule, the same diagram that regulates the price of an Uber ride decisively influenced these elections. Yet to focus solely on the conviction of Cambridge Analytica or on Facebook’s internal deliberations—isolating manipulation and democratic “misadventure” as the fault of particular actors—would be only a partial response, falling short of critical reflection on digital materialities and the actants involved. The more pressing issue concerns the absorptive power of platforms to process the very evidence of users’ existence: recognizing patterns, anticipating activity, organizing antitheses in truth regimes and psychoneurological states, and programming flows.

To return to the earlier example: there was a periodic affective event (the U.S. elections) and a punctual one (the suffrage result) in the delicate cause–effect relation between Cambridge Analytica and its clients, altering the trajectory of civil society and its institutions. This relation is neither the endpoint of platform modulation nor its most pernicious effect, despite its importance. Rather, the constitution of a user affectively overloaded by digital signs—and the experiential void that follows—forms the breeding ground for extracting value from what little remains of emergent behavior. Recognition of patterns here amounts to infinitesimal extraction of what is not yet given by the user—their desire—and their community. Likewise, the modeling of emergent events such as meme propagation or the formation of conspiracy groups is incorporated into the statistical variation of the norm.

Reduced to the consumption and production of digital signs, the elements that shape users’ experience—epistemologies, memories, relationships—adapt to the programming of each platform’s flows. Social, identity, and economic life are thus fatally adrift within sociotechnical networks that both associate and stimulate affection and capitalism in individual actions, from interfaces (which guide vision, writing, and reading pace) to the algorithmic opacity that privileges certain narratives while effectively censoring others. In other words, the intellectual-affective activity through which users co-construct reality becomes subsumed under the Boolean and mathematical logics of platforms.

Addressing such events solely in terms of “manipulation”—as in the cases of Brexit or Trump’s election—proves problematic, since a subject susceptible to manipulation is situated in discursive regimes, which are less fragile than the materialities that sustain the user. To manipulate is to deceive someone, reducing them, even briefly, to the condition of a tool. A user, however, is already integrated, to varying degrees, into the very platforms in which they consume, work, and inhabit. For that reason, if Cambridge Analytica or Steve Bannon did manipulate anyone, it was not the users but the platform itself. In a non-deterministic sense, one could say the outcome of such events indicates a “manipulation” of a subset of Facebook users, producing a statistical anomaly. Yet to frame the matter only in terms of manipulation obscures the deeper and more entrenched questions of modulation and control that render such events possible—even if their consequences appear reasonable and transparent.

De-responsibilization

Nevertheless, electoral disruptions are not isolated phenomena. Two political forces—sometimes equivalent and synergistic, once opposed and conflicting—stood out in the last decade: the hyper-liberalism of Silicon Valley, as founder and shaper of digital platforms, and national-capitalist neoconservatisms, both emerging from and nourished by the infocommunicational decentralizations and monetization generated by those same platforms. Understanding this new and complex historical movement (apparently antithetical and still in formation) is crucial, particularly with respect to the public sphere and the challenges of human rights. Out of tribalization (bubbles) and the automation of the public sphere arises an (un)civil neoconservative society, with emotional and (ir)rational interpretations of reality that bring implosions and assaults on democratic structures. This problematic constellation today defines the phenomena of tyranny and digital dictatorship (HARARI, 2018), shaped by the automated public sphere and the struggles—both social and parliamentary—over social media responsibility.

These developments did not emerge spontaneously; they required the active work of various agents to produce and disseminate narratives, culminating in a decisive rupture. From the creation of Facebook groups devoted to conspiracy theories, pseudoscience, and denialist counter-stories to the current proliferation of multiform, barbaric, and anti-Enlightenment discourses, the terrain has shifted. These discourses also paradoxically intertwine free speech, democracy, fascism, and medievalism. The problem is thus complex and, increasingly, judicial: who is responsible? From the perspective of the hyper-liberals who own digital platforms—and who have an explicit interest in maximizing content circulation while minimizing responsibility—any discursive or visual material becomes acceptable, so long as it does not interrupt the continuum of user engagement and stimulation. The goal is to induce users to express themselves, while simultaneously concealing the diagrammatic operation of machinic enslavement that underpins this process—an operation that purports to liberate individuals from overt forms of social subjection (LAZZARATO, 2014).

Above all, in the contemporary cybernetics of bodies, the human being is reshaped by a renewed reality and redefined relationships between individuals. The current control diagram is tied to a cybernetics synthesized in the data produced through online interaction—data mined as soon as the programming of flows identifies meaningful relations across series, approaching what Chun (2016) calls the “pathologization of habits.” From the perspectives of computer science and engineering, and under the guise of the platforms’ so-called “technological neutrality,” such relations generate new meanings of human presence and machinic logics of existence: patterning, relevance, anticipation, valorization, aggregation, programming, determination, concealment, and marginalization. The dynamic is not unlike that of the railways in the First Industrial Revolution: surplus value and profit. Today, however, these appear as machinic surplus-value and user “monetization” within the platform economy.

Depriving and watching

The veil and exemption provided by platforms’ so-called “technological neutrality” are purely ideological maneuvers. Academically, the first critiques and unveilings came especially from debates on surveillance and privacy. Although these raise obviously relevant issues—particularly in a post-WikiLeaks and Snowden world—surveillance and privacy were initially tied to centralized topologies of power and to Orwellian, disciplinary imaginaries. The rise of digital platforms and their absorption of prior info-economic infrastructures, however, has induced a subtle yet ongoing shift in the modulation of the self at both micro and macro levels. This shift has generated the need to rethink privacy (and surveillance) from other perspectives.

Privacy can be conceived as the right of an individual—a distinct body recognized as a whole by institutions—to selectively erase traces of its existence in order to be protected from others. Such traces may be made visible through telecommunications, textual residues, or other forms of memory exteriorization. In this sense, one can consider, alongside the notion of individuality, the structures and infrastructures that can be rendered opaque to others and to institutions: walls, windows, curtains, untapped telephone lines, keys, phone passwords, bank accounts, to name just a few. A house’s architecture shelters a body that experiences reality one moment at a time. Telephone lines mediate dialogue between two individuals. Keys and passwords presuppose single-use and non-transferable ownership. All these technologies reinforce a narrow liberal notion of exclusive possession—at once evidence of and decoy for concepts such as autonomy, freedom, and dignity.

Corporate “philosophies” themselves provide symptomatic clues. In a recent conference about Facebook’s future, its CEO condensed the company’s new direction into the slogan: “The future is private” (STATT, 2019). In English, “private” may mean “particular,” but it also connotes “ownership.” This is perhaps the tricky point in Zuckerberg’s prophecy: it recognizes the double value of data, at once residue of the intimate sphere that encompasses the user and their affinity groups, and raw material to be commercialized as private property—sold, processed by algorithms, and transformed into products. The slogan also appeals to users’ supposed autonomy over their data, even as their data are expropriated. In fact, as Chun reminds us: “Privatization is destroying the private, while also fostering state surveillance and security as house arrest” (CHUN, 2016, p. 12).

Bruno (2006) had already discussed the technopolitics of surveillance emerging with new internet infrastructures, emphasizing the production of the “digital double.” This double is created through user profiling, derived from the extraction of their relationships with inhabited infrastructures, in order to project tendencies. Actions can then be taken before the probabilities indicated by the data materialize, effectively implementing a foreseen future. The digital double is thus a set of data that precisely composes the user’s disintegration: a spectral reflection reduced and adapted to .json and .xml spreadsheets and files.

It is well known that the probabilistic and predictive actions of modulation mechanisms have established unprecedented forms of media agenda-setting and framing. Broadcast has been replaced by pointcast, aiming—through marketing strategies—at deprivation and surveillance, reducing the potential for individuation while creating “multiplicities without alterity” (ROUVROY; BERNS, 2013). In this way, surveillance devices are not repressive or exclusionary technologies. Rather, in line with the neoliberal horizon, they acquire a positive valence by allowing bodies to express and speak, accounting for their gestures, and ultimately producing both enchantment (pathological habituation) and profit.

Thus, if the new “Industry 4.0” of data extraction, prediction, use, and sale is fertile and prosperous—marked by an unprecedented concentration of wealth in the history of capitalism—it is due above all to the emergence of digital platforms. These platforms have instituted deprivation and surveillance as innovative modes of capturing and controlling human life, no longer exclusively tied to or subordinated by state power, but instead forming a crucial neuralgic point of capitalist deterritorialization.

Anarcho-capitalism

Contemporary corporations distinguish themselves from earlier ones through the diffuse ways in which they inject and regulate modulations—such as advertising—transforming them into the contemporary moral language. It can be said that the modulation mechanisms of digital corporate platforms intensify the anarchic expedients of capitalist deterritorialization, capable of continuously imploding and expropriating the powers of the State and the public sphere, while simultaneously promoting a new order characterized by refeudalization and the cybernetic neocolonialism of the world. This constitutes the present unfolding of the historical phenomenon that, for nearly half a century, has been referred to as neoliberalism.

At the genesis of this historical phenomenon, one book anticipated with remarkable depth the scope and implications of capitalist deterritorialization: Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (DELEUZE; GUATTARI, 2013 [1972]). For its extraordinary concision, the following two excerpts are particularly worth noting:

Never before has a State lost so much of its power in order to enter with so much force into the service of the signs of economic power. And capitalism, despite what is said to the contrary, assumed this role very early, in fact from the start, from its gestation in forms still semifeudal or monarchic-from the standpoint of the ow of “free” workers: the control of manual labor and of wages; from the standpoint of the ow of industrial and commercial production: the granting of monopolies, favorable conditions for accumulation, and the struggle against overproduction. […] In short, the conjunction of the decoded flows, their differential relations, and their multiple schizzes or breaks require a whole apparatus of regulation whose principal organ is the State (Idem, p. 252-3).

The rhetoric of deregulation is an ideological fallacy—one of the hallmarks of contemporary (and cynical) anarcho-capitalism. The government and corporations operate in symbiosis, exchanging sovereign and regulatory roles so that public debates and responsibilities are addressed, emptied, weakened, and ultimately submitted to diffuse capitalist operations. Disruptions produced by digital platforms create the conditions that make this possible.

In 2014, The Invisible Committee (2015), drawing on the legacy of Deleuze and Guattari, anticipated several crucial impasses. The following passages are equally concise and illustrative:

Absorbed in our language-bound conception of the public thing, of politics, we have continued debating while the real decisions were being implemented right before our eyes […]. Contemporary power is of an architectural and impersonal, and not a representative or personal, nature […]. Power is now immanent in life as it is technologically organized and commodified (Idem, p. 84-5).

A possible amendment, in conclusion: unlike an architecture—which resembles the body’s confinement and training devices—power today has a virtual, shapeless, and capillary diagrammatic nature. It follows mutant patterns and employs schemes of antithetical forces, administering and serving lives under the guise of complete “freedom of speech.” Contemporary digital platforms and their data centers are formidable machines for accelerating and controlling flows, energies, investments, and speculations, decomposing existing forms of the State and the public sphere. In this context, the fundamental predicate of these applications is the population of subjectivities over time, along with the growing constitution of associated means that tend to satisfy, consign, and resign the “users.”

Political litigation is not limited to public accountability. The remaining question concerns control—its limits and the mechanisms to contest it. As McQueen (2016, p. 4) observes: “Control is a relative advantage, a process of constant, yet contestable, refinement and rearrangement of mechanisms.” Control technologies tend to exhaust subjects’ nervous systems with perennial reward circuits, producing pathological habituation and preordaining dispossession, insofar as they broker various operative simulacra, exploiting moribund liberalism rooted in the bourgeois notions of privacy and property.

The ideological veil ultimately reflects the absence of a materialist and political organological approach that genuinely addresses computational software mechanisms and practices, creating alternative operational designs and offering potential answers to Catherine Malabou’s famous inquiry: What should we do so that consciousness of the brain does not purely and simply coincide with the spirit of capitalism?

If capitalism has become fundamentally a machinic operativity of affect (and debt) rather than ideology and sovereignty, the effective struggle is, above all, for digital materialism: the production of political organologies capable of effectively decentralized public spaces and self-management, interrupting the authority of cybernetic feudal lords.

References

BRUNO, Fernanda. Dispositivos de vigilância no ciberespaço: duplos digitais e identidades simuladas. Revista Fronteiras: estudos midiáticos, São Leopoldo, v. 8, n° 2, p. 152-159, maio 2006.

CHUN, Wendy Hui Kyong. Updating to Remain the Same: Habitual New Media. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2016.

COCCIA, Emanuele. O Bem nas Coisas: a publicidade como discurso moral. Lisboa: Documenta, 2016.

THE INVISIBLE COMMITTEE. To Our Friends. South Pasadena, CA: Semiotext(e), 2015.

DARVILLE, Jordan. Spotify CEO Daniel Ek says working musicians may no longer be able to release music only “once every three to four years”. In: The Fader. Nova Iorque, 30 jul. 2020. Available at: https://www.thefader.com/2020/07/30/spotify-ceo-daniel-ek-says-working-musicians-can-no-longer-release-music-only-once-every-three-to-four-years, accessed April 3 2021.

DELEUZE, Gilles; GUATTARI, Félix. Anti-Oedipus: capitalism and schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003.

DELEUZE, Gilles. Foucault. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2006.

GALLOWAY, Alexander R. The Poverty of Philosophy: Realism and Post-Fordism. Critical Inquiry, v. 39, issue 2, Winter 2013.

HARARI, Yuval Noah. Why Technology Favors Tyranny. The Atlantic, October 2018. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2018/10/yuval-noah-harari-technology-tyranny/568330/, accessed April 03 2021.

LAZZARATO, Maurizio. Signs and Machines: Capitalism and the Production of Subjectivity. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2014.

MALABOU, Catherine. What Should We Do With Our Brain? New York: Fordham University Press, 2009.

MASSUMI, Brian. Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation. Durham: DUP, 2002.

McQUEEN, Sean. Deleuze and Baudrillard: From Cyberpunk to Biopunk. Edinburgh: EUP, 2016.

NOBLE, Safiya Umoja. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. Nova Iorque: New York University Press, 2018.

PASQUINELLI, Matteo. Google’s PageRank Algorithm: A Diagram of the Cognitive Capitalism and the Rentier of the Common Intellect. In: BECKER, Konrad; STALDER, Felix (org.), Deep Search: The Politics of Search Beyond Google. London: Transaction Publishers, 2009.

ROUVROY, Antoinette; BERNS, Thomas. Algorithmic governmentality and prospects of emancipation: disparateness as a precondition for individuation through relationships? Réseaux – Communication – Technologie – Société, Paris, v. 177, n°1, 2013, p. 163-196.

SAVAT, David. Deleuze’s objectile: from discipline to modulation. In: POSTER, Mark; SAVAT, David. Deleuze and New Technology. Edinburgh: EUP, 2009, p. 45-62.

SAVAT, David. The Uncoding the Digital: Technology, Subjectivity and Action in the Control Society. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

STATT, Nick. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg says the ‘future is private’. In: The Verge. April 30 2019. Available at: https://www.theverge.com/2019/4/30/18524188/facebook-f8-keynote-mark-zuckerberg-privacy-future-2019, acessed April 3 2021.

SULLEYMAN, Aatif. Netflix’s biggest competition is sleep, says CEO reed hastings. In: The Independent. London, April 19 2017. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/gadgets-and-tech/news/netflix-downloads-sleep-biggest-competition-video-streaming-ceo-reed-hastings-amazon-prime-sky-go-now-tv-a7690561.html, accessed April 3 2021.